Protect Your Garden the Organic Way

Avoiding chemical pesticides in your home lawn and garden is a great step to ensuring the health and safety of your family, pets, neighborhood, and the earth!

By the time you notice holes in leaves, weak stalks, and rotten fruit, pests have already won the battle with that plant in your garden. Understanding pests’ lifecycles and habits and using smart gardening strategies will prepare you to prevent pest damage before it happens. We have also gathered non-chemical solutions for dealing with a pest after it has already made a home in your lawn or garden.

Why is it Important to control Pests the Organic Way?

Often we react to seeing weeds or pests by immediately applying chemicals, or even apply chemicals as prevention.

Exposure to pesticides has been linked to a long list of diseases and health problems: Parkinson’s, infertility, cancer, birth defects, encephalitis, and lymphoma, just to name a few. Another problem is that the law does not require companies to test lawn pesticides with the same standards as pesticides used on commercially-grown food. Many of these contact hidden “inert ingredients” that have never been tested for possible harm. The Center for Disease Control has documented cases of farmworker illness after exposure to pesticides.

In addition to the harm they can do to us humans, pesticides contaminate the air, water, soil, plants, and animals around us. For example, many studies have proven that pesticides harm honeybees, butterflies, ladybugs (which eat lots of other pests), and fish, and that lawn chemicals seep into the water table.

Besides that, they can be expensive!

Learning to combat pests without chemicals is a great way to help your health and that of your neighbors and the environment.

An important thing to consider is that healthy organic soil is an easy way to reduce pests in the first place. Plants tend to thrive in an organically rich environment, which helps them fight off pests on their own. If you don’t already have one or more compost bins for composting at home, get one. It also wouldn’t hurt to have a compost pail to keep near the kitchen sink to collect vegetable scraps conveniently.

Orange Guard is a non-toxic organically approved bug killer. The active ingredient d-Limonene (orange peel extract) destroys the wax coating of the insect’s respiratory system. When applied directly, the insect suffocates. https://amzn.to/3gUPRka

This OMRI listed organic insect killer and repellent for your lawn and garden that attaches to a water hose for easy application. It kills and repels bugs. https://amzn.to/3iZWLWY

An organic, non-toxic killer for the natural control of Japanese Beetle grubs. https://amzn.to/3iZ0V1q

More About Avoiding Chemical Pesticides

Links to more information about pesticides and what you can do to avoid them.

- Beyond Pesticides – Fact sheets about specific chemicals and what to do in a pesticide emergency. “Least Toxic” solutions for common household and garden pests.

- Northwest Coalition for Alternatives to Pesticides – News on pesticide-related issues and healthy solutions to pest problems.

- Pesticide Action Network Pesticide Database – A database of pesticide toxicity and regulatory information. Reference section provides general information about pesticides and their health effects.

- Food News – Offers a downloadable wallet card to help you choose produce that lowers your exposure.

General Organic Gardening Strategies Can Help Protect Your Garden From Pests

You may have heard of Integrated Pest Management and wondered what it meant. Integrated Pest Management is a fancy way to describe the practice of planning and working in your lawn or garden to prevent weeds and pests, using chemicals only as the last resort. Here are some basic steps:

1. Learn about the plants and the weeds and bugs that affect them.

2. Choose the right plants. Plant native species whenever possible. Native plants are better protected by their own “immune systems” and their relationships with other plants and animals in the area. You may also look for plants that are pest-resistant. Diversifying the garden with a variety of plants will help the plants protect each other from pests. For example, small flowered plants like daisies, mint, and rosemary attract many insects that eat the pests. Check with a local garden shop or nursery for recommendations.

3. Maintain healthy, fertile soil by rotating your plants, adding compost, and mulching.

4. Plant early to avoid the worst bug season.

5. Allow growth of the pests’ natural predators. Ladybugs, ground beetles, and birds eat many pests, and fungi and moss can infect the pests naturally. Spraying chemicals often kills the beneficial bugs too.

6. Get out there and work with your hands! A hoe, spade, and your hands are the best tools to combat weeds. Getting close to your plants will help you identify problems and remove pests and damaged plants by hand. Tilling can eliminate many weeds as well. Pruning plants helps remove diseased parts, leaving the plant’s nutrients for the healthy parts. Always prune back to a main branch or stem; leaving “stubs” opens a door for pests.

7. Keep a garden journal in which you record when you see pests, what they look like, what they have done to the plants, and the actions taken. In this way, you will learn what works and what doesn’t while experimenting with new techniques.

Specific Garden Pests and How to Control Them

Peach Borer

Location

The peach borer is a native of North America, found wherever peaches are

grown east of the Rocky Mountains. A closely related species dwells in

the West

Vulnerable plants

It is most important insect enemy of peach trees, but also attacks plum,

wild and cultivated cherry, prune, nectarine, apricot and various

ornamental shrubs.

Peach Borer Appearance and Habits

The first sign of injury is usually a mass of gum and brown frass at the base of the tree trunk, indicating that white worms, with brown heads, are working in the bark, anywhere from 2 to 3 in. below ground to 10 in. above. The winter is passed in this larval stage; in spring the borers resume feeding, attain their full inch-long size, then work to the surface of the bark to form cocoons of gum, excrement and bark particles.

Shortly before moth emergence, brown pupa cases are forced partly out of the cocoons. The moths are a little over 1 in. across their wings; the males are blue, with transparent, blue-bordered wings; the females have an orange band around a blue abdomen, blue fore-wings, transparent hindwings. Each female lays several hundred eggs near the base of the tree trunk, young worms hatching in about ten days to work their way inside the bark. Peaches seldom survive repeated borer attacks.

How to Manage Peach Borers

Dig out the borers when you notice their gummy residue around the base of the tree.

When planting peach trees, make a tin “shield” that circle the tree and fill the space between the shield and tree with tobacco dust. This forms a protective pesticide layer.

You can also encircle trees with moth balls or soft soap.

Coat bark of new trees with Tanglefoot of Stickem.

Plant garlic near the trees.

Squash Borer

The squash vine borer is a native of this hemisphere, occurring east of the Rocky Mountains from Canada to Brazil.

Vulnerable Plants

It attacks squashes and pumpkins and occasionally gourds, melons and cucumbers.

Squash Borer Appearance and Habits

The insect winters as a larva or pupa inside a silk-lined dark cocoon an inch or two below soil level. The adult is a wasplike moth, with copper-green forewings and orange and black abdomen, appearing in June in the Middle Atlantic States. It lays 150-200 eggs, singly, on the stem, especially at the base of the main stem, leaf stalks, blossoms. The young borers hatch in about a week, tunneling into the stem to feed. Usually the first sign of their presence is a sudden wilting of the vine, at which time close examination discloses masses of greenish-yellow excrement protruding from holes in the stem. The borer, a white, wrinkled caterpillar about 1 in. long, can be seen by slitting the stem with a knife.

How to Manage Squash Borers

Baby blue and butternut squash can resist the borer to some degree.

If a change in location is possible, do not grow squashes two years in succession on the same ground. If the same area must be used, spade or plow it in the fall to expose the cocoons. Pull up and burn vines immediately after harvest.

If a vine starts to wilt, kill the borer with a knife and heap earth over the stem joints to start new roots.

Make a second planting of summer squash to mature after the first borer brood has disappeared.

Apple Maggot

Location

The apple maggot or railroad worm is a native, extending from Canada to North Carolina and west to North Dakota and Arkansas.

Vulnerable Plants

The maggot is particularly injurious to summer varieties in northern

sections of the country. It also attacks blueberries, plums, and related

flies infest peaches, cherries, and walnut trees.

Apple Maggot Appearance and Habits

Hibernation takes place inside a small brown puparium buried 1 to 6 in. deep in the soil. The adult flies do not emerge until summer (late June in some sections, early July in most). They are a little smaller than house flies, black, with white bands on the abdomen and conspicuous zigzag black bands on the wings.

The females lay their eggs singly through punctures in the apple skin; in 5 to 10 days these hatch into legless whitish maggots which tunnel through the fruit by rasping and tearing the pulp into brown winding galleries. Early varieties soon become a soft mass of rotten pulp; later varieties have corky streaks through the flesh and a distorted pitted surface. Completing their growth about a week after the apples have fallen to the ground, the larvae leave the fruit and burrow in the ground to pupate.

Ordinarily pupation continues until the next summer, but in its southem range, the apple maggot may have a partial second generation.

How to Manage Apple Maggots

Immediately remove and destroy dropped fruit on a large scale; this is

effective only if implemented over several acres. If the fruit is not

too badly infested, it can be turned into cider.

Plant white clover, home to beetles.

Hang fly-traps in trees from mid-June through the harvest, baited with a mixture of molasses, water, and yeast.

Maggots in picked fruit may be killed by holding the apples in cold storage for a month.

Codling Moth

Codling Moth Location

The codling moth, or apple worm, came to this country from Europe about 1750 and quickly became our most destructive pest of apple fruit.

Vulnerable Plants

Codling moths also attack pears, apricots, cherries, peaches, plums,

quinces, crabapples and, in California, English walnuts. Unfortunately,

spraying with pesticides is often the only effective method of

controlling the codling moth, which is why these fruits are the most

highly-contaminated with pesticides.

(http://www.foodnews.org/reportcard.php)

Codling Moth Appearance and Habits

The insect passes the winter as a full-grown larva, an inch-long pinkish-white caterpillar with a brown head, inside a silken cocoon under loose scales on apple bark or in other sheltered places. In spring the worms change to brown pupae and then grayish-brown moths, 3/4 in. across the wings. These emerge to lay their eggs, singly, on the upper surface of leaves, on twigs and on fruit spurs. They work at dusk, when the weather is dry and the temperature is above 55° F.

A cold, wet spring at the time of egg-laying means less trouble with wormy apples. Hatching in 6 to 20 days, small worms crawl to the young apples, entering by way of the calyx cup at the blossom end. They tunnel to the core, often eating the seeds, then burrow out through the side of the apple, leaving a mass of brown excrement behind, and crawl to the tree trunk to pupate. There are two generations over most of the United States, and in some places a partial third. Second-brood larvae enter the fruit at any point, without preference for the blossom end.

Crop reduction comes not only from wormy fruit but from early drop of immature apples and from “stings” – small holes surrounded by dead tissue which lower fruit value even though the worms are poisoned before doing further damage.

How to Manage Codling Moths

Plant cover crops that support moth-eating beetles.

Hand-remove and destroy larvae.

Band trees with parasitic nematodes.

Clean up the orchard by scraping loose bark from trees and removing rubbish and all dropped apples immediately.

Spotted Cucumber Beetle

Spotted Cucumber Beetle Location

It is found throughout the United States east of the Rocky Mountains, increasing in importance towards the South.

Vulnerable Plants

The spotted cucumber beetle, aka Southern Corn Root-worm or Budworm, belongs to the same genus as the striped beetle but is a much more general feeder. As an adult, it works on at least 200 vegetables, flowers, weeds and grasses, and as a larva, feeds on roots of corn, beans, small grains, wild grasses. An almost identical variety, often called the Diabrotica beetle, is an important flower and vegetable pest in California.

Spotted Cucumber Beetle Appearance and Habits

The greenish-yellow beetles, 1/4 in. long with 12 conspicuous black

spots, hibernate in protected places under rubbish or at the base of

plants. In spring females lay their eggs just below the ground surface

on or near young corn plants; yellow-white worm-like larvae with brown

heads hatch to burrow into roots and bud. The corn either makes poor

growth or dies. As they feed, the larvae also may disseminate bacteria

causing corn wilt.

Although spotted cucumber beetles do not cause as much damage to cucurbit foliage as the striped beetles they, too, are carriers of cucumber wilt and mosaic. They are also particularly destructive to flowers, being a common pest of dahlias, cosmos, chrysanthemums and other late bloomers.

How to Manage Spotted Cucumber Beetles

Avoid injury to the corn crop by planting late on land plowed

the previous fall. For cucurbits follow directions given for striped cucumber beetles.

Striped Cucumber Beetle

Striped Cucumber Beetle Location

The striped cucumber beetle is a native of the United States, with a range from Mexico to Canada east of the Rocky Mountains.

Vulnerable Plants

It is a serious pest of the cucurbit family, injuring cucumbers,

muskmelon, winter squash, pumpkins, gourds, summer squash and watermelon

about in that order.

Striped Cucumber BeetleAppearance and Habits

The winter is passed as an adult – a small, 1/4 in. long yellow beetle with three black stripes, hiding at the base of weeds or under trash, often at some distance from the vegetable patch. The beetles start feeding in early spring on blossoms and leaves of various wild plants, but they migrate to the vine crops as soon as these appear above ground.

Mating soon after migration, the females lay yellow eggs, in crevices in the ground, which hatch into small, worm-like, whitish larvae. These feed on the roots for 2 to 6 weeks, pupate in the soil and, by midsummer, produce beetles which feed on leaves and often fruits until fall. There is one generation in the North, two or more in the South.

Cucumber beetles are injurious not only by the feeding of adults on leaves, stems and fruits, and of larvae on the roots, but also because they are carriers of cucumber wilt bacteria and the mosaic virus. The bacteria, living over the winter in the beetle’s intestinal tract, are inoculated into plants as the beetles feed; the virus is acquired while the insects are feeding on weeds in the spring and then transmitted to the vine crops.

How to Manage Striped Cucumber Beetle

Plant late, after the first beetles hatch. Start plants indoors in containers.

Protect seedlings with cheesecloth or nylon tents made by draping cloth over crossed stakes.

Straw mulch keeps adults from walking between plants.

Braconid wasps, nematodes, and soldier beetles consume the cucumber beetle.

Squash Bug

Squash Bug Location

The squash bug is common throughout the United States, ranging from Central America to Canada.

Vulnerable Plants

The squash bug attacks all vine crops, showing a preference for squashes and pumpkins.

Squash Bug Appearance and Habits

The adult bug is dark brown, sometimes mottled with gray or light brown, hard-shelled, about 4″ long. Because it gives off a disagreeable odor when crushed it is commonly called a “stink bug,” but true stink bugs belong to a related family. Unmated adults hibernate in the shelter of dead leaves, vines, boards or buildings and fly to the garden when the vines start to “run.” Mating takes place at that time, and clusters of brownish eggs are laid on the underside of the leaves in the angles between veins. Egg-laying continues until midsummer. The eggs hatch in a week or so into young nymphs with green abdomens and crimson heads and legs, but older nymphs are a somber grayish white with dark legs. There are five nymphal instars, or periods between molts, in the two months before the winged adult form appears.

Squash bug feeding causes leaves to wilt, then turn black and crisp. Small plants may be killed entirely, larger plants have one to several runners affected. Sometimes bugs are so numerous that it is impossible to produce any squashes; sometimes they congregate in dense groups on unripe fruits.

How to Manage Squash Bug

Keep squash bugs away from vine plants by also planting marigolds, radishes, or nasturtiums.

Squash bugs like to hide under boards or trash, wherever it is darka and damp. Remove all potential protection.

Rotate crops.

Handpick beetles and eggs.

June Beetle

June Beetle Location

June beetles, aka June bugs, daw bugs, May beetles, and white grubs, include about 200 species and are distributed throughout North America.

Vulnerable Plants

More than 200 species injure grasses and vegetables in the grub stage

and trees as adults. Adult beetles eat leaves of oak, ash, birch, pine

and other trees, as well as blackberry leaves. Grubs attack roots of

corn, potatoes, soybeans and strawberries.

June Beetle Appearance and Habits

Most beetles have a three-year cycle. Large, dark-brown beetles and white, brown-headed grubs winter in the soil. In spring adults leave the soil at night, flying to feed on leaves, mating, and returning at dawn to lay round white eggs in grassland soil. The grubs hatch in two or three weeks and feed on roots until fall when they work their way below the plow-line for winter.

Working upwards the next spring, they do most of their damage this second season. They grow to about an inch long, being the largest grubs commonly found in soil. The third season they feed until late spring, pupate in soil, change to beetles in late summer, but do not leave the ground until the next spring. Heavy beetle flights are to be expected every third year, but since there are different broods at varying stages in the life cycle, some June beetles appear every spring.

How to Manage June Beetle

Rotate berries with deep-rooted clover and alfalfa.

Tear up infested lawn and grasses, treat with organic fertilizer, and till and plow deeply to destroy the grubs the summer before planting.

Handpick adult beetles.

Japanese Beetle

Japanese Beetle Location

The Japanese beetle was first noticed in this country in 1916, near Riverton, N. J. Presumably it came from its native Japan as a grub in soil around the foots of nursery stock, or perhaps in a shipment of iris or azaleas. Since its discovery this pest has spread naturally from five to ten miles a year, to cover from Maine to Georgia, and west to Michigan and Missouri.

Vulnerable Plants

Adult beetles feed on foliage, flowers and fruits of almost 300 plants,

and grubs work on grass roots. Some of the beetle’s favorite foods

include: shade trees such as elm, horse chestnut, linden, sassafras,

white birch, willow; fruits – grapes, raspberries, peach, apple, plum,

cherry, quince; flowers – rose, hollyhock, marigold, mallow, spiraea,

zinnia; vines – especially Virginia creeper; vegetables – corn, soybean,

asparagus, rhubarb.

Japanese Beetle Appearance and Habits

The beetles are about 1/2″ long, shining bronze-green, with bronze wing covers from under which protrude twelve tufts of white hairs. They are particularly active on warm days, congregating in crowds on the sunniest parts of plants. They are most active on warm, sunny days, and fly only in the daytime. They emerge in late spring and early summer, and are most active for four to six weeks. Seasons following a particularly wet summer usually bring a bigger population of beetles.

During this time, each female lays from 40 to 60 eggs 2 to 6 inches deep in the soil. The young grubs feed on grass roots until cold weather, when they work their way down below the frost line. The grubs are white, hairy, brown-headed 3/4 in. long.

Beetles leave only the veins of leaves, and devour entire flower and fruits. Grubs cut off grass roots so that the sod can be rolled back like a carpet. Beetles feeding on corn silks prevent pollination, resulting in sparse kernel development.

How to Manage Japanese Beetles

The Japanese beetle has many natural enemies: the spring and fall typhia wasps, birds, and skunks are helpful beetle enemies.

Avoid planting turf or sod from outside the area, which may lack the nutrients to support these natural enemies.

Milky spore disease is harmless to plants, animals, and humans, but deadly for the beetle. It is most effective in areas bigger than one acre. Talk to a local garden group or county representative for more information.

Remove diseased fruit from the trees and ground, and keep the area weeded and clean.

Larkspur is poisonous for the beetles, and they avoid the odor of geraniums.

Handpick the beetles and drop them into a bucket of water with a think layer of kerosene.

Traps painted yellow and baited with fermenting fruit, sugar, and water catch thousands of beetles – empty this daily.

Colorado Potato Beetle

Colorado Potato Beetle Location

The Colorado Potato Beetle is a native, and is so common that it is referred to as simply the “Potato Bug.” Found in the Rocky Mountains feeding on Buffalo Bur about 1923, it did not become abundant until the potato was introduced into its territory. Then it spread eastward from potato patch to potato patch, averaging 85 miles a year, until it reached the Atlantic Coast and invaded Europe.

Vulnerable Plants

Although potato is its preferred food, this beetle will eat almost anything available, especially tomato, eggplant, tobacco, pepper, ground cherry, thorn apple, jimson weed, henbane, and thistle.

Colorado Potato Beetle Appearance and Habits

Adults spend the winter buried 8 to 10 inches deep in the soil, emerging

in time to feed on the first foliage of early potatoes. They are wide,

convex beetles, 1/2″ long, with alternating black and yellow stripes.

Females lay up to 20 batches each of orange-yellow eggs in groups on the

underside of the leaves, over 4 to 5 weeks. The eggs hatch into

humpbacked, purplish-red larvae, with 2 rows of black dots along each

side. These larvae eat voraciously, often entirely consuming the leaves.

When full-grown they descend into a spherical cell in the ground,

transform to a yellowish pupa, and in 5 to 10 days new adults emerge to

feed and lay eggs for the second generation.

How to Manage Colorado Potato Beetles

Grow potatoes above ground! Drop potato seeds on 3″ of sod or leaf cover and cover with straw.

Plant natural beetle repellents nearby: flax, horseradish, garlic, eggplant, snap beans, nightshade.

Handpick the beetles and crush the eggs.

Dust the tops of potato leaves with wheat bran. The beetles will eat it and bloat up until they die.

Ladybugs and toads eat beetles.

Spray with basil water.

Spray foliage thoroughly with lead or calcium arsenate, or cryolite, whenever beetles or larvae are present. Either arsenical may be combined with Bordeaux mixture for the control of blight, but cryolite may be used only with a fixed copper free from lime.

Asparagus Beetle

Asparagus Beetle Location/Vulnerable plants

The Asparagus Beetle arrived in this country from Europe about 1856 and is now widely distributed. Larvae and adults gnaw succulent shoots and devour summer foliage, weakening the plants for another year. Asparagus is, apparently, the only host.

Asparagus Beetle Appearance and Habits

The beetles are less than 1″ long, bluish-black, with red thorax, blue and yellow wing covers, the yellow often present as spots. They winter in any protected place, often in trash left around the garden, garages, and homes. As soon as asparagus shoots appear in spring, they begin to feed and lay rows of dark-brown eggs. Gray, black-headed slugs come out in 3 to 7 days, chew on the stems for 10 to 14 days, then pupate in the ground for about a week. The beetles emerge and lay eggs either on stems or foliage. There are at least two generations in the North, more in the South.

The 12-spotted Asparagus Beetle is orange to brick red with, yes, 12 black spots. This species feeds on the shoots, but delays egglaying until shortly before the berries form, when they glue dark green eggs to the leaves. The orange larvae and second generation beetles feed only on the berries.

How to Manage Asparagus Beetles

A clean garden is the best prevention. Eliminate any places the beetle can hide, and till the soil to rouse them from hibernation.

Asparagus beetles do not like tomato plants, and asparagus plants kill the nematodes that often attack tomatoes. Intersperse the plants so that they protect each other.

A cheesecloth netting can protect tender young asparagus.

Birds, chickens, and ducks love to eat the asparagus beetle, and ladybugs and the chalchid wasp feed on the larvae.

Cut the asparagus shoots every 2 or 3 days, before the eggs can hatch.

Dust asparagus with bone meal or rock phosphate.

The spotted asparagus beetle cannot fly in the morning, and can be handpicked.

Elm Leaf Beetle

Elm Leaf Beetle Location/Vulnerable Plants

The Elm Leaf Beetle is believed to have reached Baltimore from Europe about 1834. It is now enormously destructive throughout New England and the Middle Atlantic States, occurs scatteringly westward to the Mississippi, and is found on the Pacific Coast. It is confined to the elm, with Chinese and Siberian elms most severely injured.

Elm Leaf Beetle Appearance and Habits

The adult beetle is 1/4″ long, yellow, changing to olive with age, with black spots on the head and a black band on the outside of each elytrum or wing cover. It winters in protected places, often in houses, and in spring flies to the elm, where it lays a double row of yellow, lemon-shaped eggs on the underside of a leaf. These hatch in about a week into black-spotted larvae, which skeletonize the leaves, eating out everything except veins and epidermis. After 3 weeks of feeding, they crawl down the trunk and pupate at the base, more beetles appearing in 1 to 2 weeks, to eat holes through the leaf. There are two or three generations a year, with the elms either entirely defoliated or covered with crisp brown leaves. Two or three years of defoliation may mean death, and always mean a weakening of the tree so that it is subject to attack by the elm bark beetle, carrier of the spores causing Dutch elm disease.

How to Manage Elm Leaf Beetles

There are no proven methods of preventing the elm leaf beetle’s attack. Protect houses and garages, and keep the beetles from wintering inside, by caulking cracks. Monitor the elms to see if the damage is serious; if so, apply a narrow band of pesticide higher than human reach. A relatively harmless homemade pesticide of 3 ozs. laundry soap to 1 gal. of water will kill larvae coming down to pupate.

Gypsy Moth

Gypsy Moth Location

The Gypsy Moth is an expensive pest of shade, forest and fruit trees, especially apple, elm, oaks, and aspen. Accidentally let loose near Boston in 1869, it now inhabits an area from the east coast to Michigan, and as far south as North Carolina.

Gypsy Moth Appearance and Habits

The gypsy moth begins as a brown, hairy caterpillar, 2 inches long, with 5 pairs of blue bumps along the back, followed by 6 pairs of red ones. They feed in June and July, stripping the trees. They pupate inside a few-threads spun on limb or tree trunk and produce moths in 17 to 18 days. The brown, yellow-marked male flies freely, but the heavy female does not use her white wings with their wavy dark markings. Egg clusters are white or yellow and covered with hairs, can be as large as 1/2″ to 1″ in diameter, and are found under tree branches, in gutters, under ledges, or any other good hiding place. Distribution is by crawling of caterpillars, wind dispersal of young larvae, or by the removal of some object, such as an automobile or railroad car, with attached egg case.

How to Control Gypsy Moths

Destroy eggs whenever possible.

In early April, wrap 2″ wide sticky barrier bands around trees. There are many commercially available products, which prevent caterpillars from climbing up the tree.

The Gypsy moth has many natural predators, such as mice, flies, beetles, and wasps.

Spray with BT, twice, 5-7 days apart.

Cabbage Maggot

Cabbage Maggot Location

The Cabbage Root-Maggot, introduced from Europe almost two centuries ago, is now a serious pest in Canada and northern United States, but does not do much damage south of Pennsylvania. It likes cool weather.

Vulnerable Plants

It is injurious to cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, radishes, turnips and other members of the cabbage and mustard family, and sometimes works on beets, celery and other vegetables. In the fall months of September and October, the larvae attack rutabagas, turnips and brussels sprouts.

Cabbage Maggot Appearance and Habits

The winter is spent as a pupa in an enclosing case (puparium), 1 to 5 ins. deep in the soil. About the time sweet cherries bloom, and young cabbage plants are set out, a small gray fly crawls out of the soil to lay white eggs at the base of the stem and on adjacent soil. These hatch in 3 to 7 days into small, white, legless maggots which enter the soil to feast on the roots, riddling them with brown tunnels. Seedlings wilt, turn yellow, and eventually die. After 3 weeks the maggot forms a puparium from its larval skin and produces another fly in 12 to 18 days. The number of generations is indefinite; ordinarily the first feeds on cabbage and its relatives, while late broods menace fall turnips and radishes.

How to Control Cabbage Maggots

Plant after June 1 to avoid major pest season.

Protect seedbeds with a cheesecloth or nylon cover to prevent egg-laying, and secure it to the ground on either side. Place a 3- to 4-in. square of tar paper around stem of each plant set out, at ground level.

It is sometimes possible to remove a seedling at first sign of wilting, wash off the maggots, and replant.

Dust red pepper, ginger, or wood ash around the stem.

Pictures

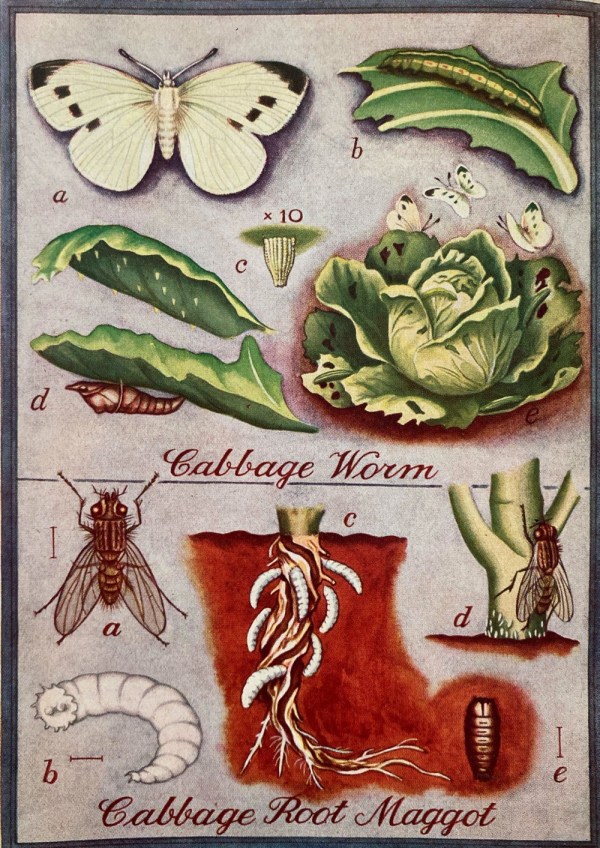

- Cabbage Roof Maggot: A. adult fly; B. legless maggot (larva)) E. puparium in soil; C. maggots working an roots; D. fly laying eggs at base of stem

Cabbage Worm

Cabbage Worm Location

The Imported Cabbage Worm came to this country from Europe, via Quebec, arriving in Massachusetts about 1869, and quickly spread to all parts of the United States.

Vulnerable Plants

It attacks all members of the cabbage or mustard family (this includes cauliflower) and also feeds on nasturtium, sweet alyssum, mignonette and lettuce.

Cabbage Worm Appearance and Habits

The insect winters in the pupa stage, a gray, green or tan angular chrysalid hanging downwards from some object near the cabbage patch. In early spring, the pupa hatches into a white butterfly with three or four black spots on each wing, a wingspan of 1 1/2″ to 2″. They lay yellow, bullet-shaped eggs singly on the undersides of leaves. In about a week, velvet-smooth green caterpillars, with alternating light and dark longitudinal stripes, hatch and start feeding, depositing pellets of dark green excrement as they eat huge, ragged holes in the leaves. They feed for 2 to 3 weeks, then pupate, there being three to six generations in a season.

How to Control Cabbage Worms

Plant tomatoes, onions, garlic, and sage around cabbage to deter the worm.

Cover plants with a lightweight nylon net to keep the butterflies from laying eggs.

Till the soil several times between plantings to destroy eggs and pupa.

Hand-remove larvae. Destroy old stalks as soon as the crop is harvested, and make sure to destroy weeds like Wild Mustard, Pepper Grass, Shepard’s Purse, on which the first-generation worms develop.

A number of natural enemies reduce the caterpillar population, among them common yellow jackets and braconid wasps. Braconid wasps are attracted by strawberries.

The cabbage worm may drown during heavy rains.

Other methods include spooning spoiled milk into the cabbage head, or spraying with a mixture of salt, flour, and water, which will make the caterpillars bloat and die.

Pictures of a Cabbage Worm, above

Cabbage Worm (Life Cycle, page 52): A. adult butterfly; B. full-grown worm (larva); C. egg, enlarged 10 times; D. chrysalid; E. typical damage by worms, adults laying eggs

Corn Earworm

Corn Earworm Location

The Corn Earworm, aka Tomato Fruit Worm, Tobacco Budworm, Cotton Bollworm, is such a successful pest that it lives practically everywhere in the world between the parallels of 50° north and south latitudes. That’s from the bottom half of Canada to almost the tip of South America.

Corn Earworm Appearance and Habits

The earworm winters as a pupa in the soil. A brownish-olive moth coming out in spring to lay 500 to 2500 eggs, one at a time, on various host plants, including weeds. The eggs are dirty white and dome-shaped. After hatching, the caterpillars grow to nearly 2″ long, have yellow heads, and vary from yellow to brown to green with lengthwise alternating light and dark stripes. There are several generations in a season; in corn, first-brood larvae eat into developing leaves, while larvae of later broods start at the silk and bore into the tip of the ear, eating the kernels down to the cob and piling up moist castings of excrement. In tomatoes the worms feed on the partially ripened fruit, restlessly moving from one tomato to another; pods of lima beans are sometimes invaded.

How to Manage Corn Earworms

Sweet corn is protected by applying mineral oil with a medicine dropper into the silk at the tip of the ear. (1/2 – 3/4 of a dropper). This should be applied after the silk turns brown.

Corn varieties with a tightly closed ear fare better at keeping the corn borer away; some farmers have aided the plants by attaching closepins to the ear tips to physically block out the worms.

Other strategies include clipping the silk every four days, and planting marigolds near the corn.

In southern gardens, the tomato fruit worm may be controlled by applying pinches of bait to the fruit clusters.

European Corn Borer

European Corn Borer Location

The European Corn Borer, discovered in Massachusetts in 1917, has spread throughout most states east of the Rockies.

Vulnerable plants

The corn borer eats more than just corn. It will bore into a wide variety of plants with large stems, stalks, and fruits, such as bell peppers, snap and lima beans, potato vines, tomatoes. It also attacks flowers: dahlias, gladiolus, and large-stemmed ornamental and weed plants.

European Corn Borer Appearance and Habits

The corn borer winters in larva form, an inch-long, flesh-colored caterpillar with inconspicuous black dots, in old stalks left around the garden and pupates in the same stalk. Yellow-brown moths appear in late May or June to lay white eggs on the underside of corn leaves over a period of 3 or 4 weeks. These eggs start hatching about a week later, and the young larvae chew small, round holes in leaves and move toward and into the plant stalk, leaving behind sawdust-like excrement on the leaves and outside the stalk. If you see bent stalks, the larvae have already done a lot of damage inside the plant.

How to Manage European Corn Borers

Uprooting, shredding, and burying infected stalks is the most successful method of destroying the corn borer because it kills the wintering larvae. Although this method does not salvage the affected plants, it will protect the next year’s harvest.

Late plantings are more vulnerable to the corn borer. Corn or other affected plants should be planted early, to grow while other plants are also bearing fruit.

Removing the borer by hand is the oldest remedy. Split the stem a little below the entrance hole and pick out the worm.

Other methods include attracting the corn borer moth to light traps, or using parasitic insects such as the ladybug, which will consume up to 60 borer eggs a day.

Spray natural pesticide BTK (http://gardenline.usask.ca/pests/bt.html) on undersides of leaves and into tips of ears after silks wilt.

Pictures of a European Corn Borer

- European Corn Borer (Life Cycle, page 51): A. adult moth; B. larva, a smooth caterpillar; C. pupa and larva inside corn stem, borer frass protruding from hole; D. female moth laying eggs on corn leaf; E. borer working in ear of corn, with frass protruding; F. borers overwintering in old corn stalks

Leave a Reply