By Julie Christensen

Native to North America, bluebells are charming woodland plants that thrive in partial to full shade. Also known as Virginia bluebells (Mertensia virginica), the plants can be found in prolific numbers in woodland areas, particularly in the eastern and Midwest United States. Bluebells were used medicinally by the Cherokee Indians to treat tuberculosis and whooping cough and as an antidote for poisoning.

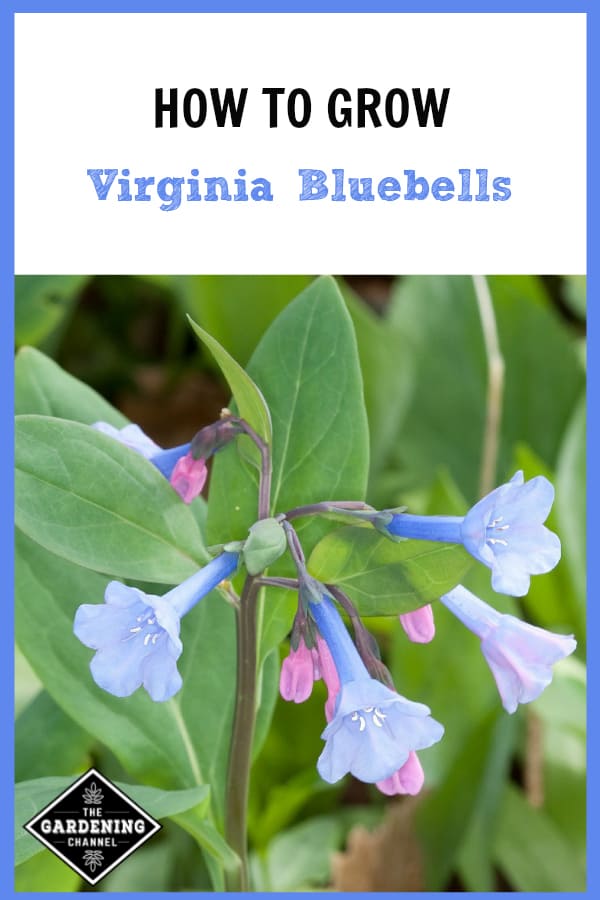

In the home garden, bluebell flowers are a valuable addition to shady areas. They bloom in spring, forming small clusters of bell-like flowers on slender stalks. The plants grow 12 to 24 inches tall with bright green foliage. During the spring, the plants grow and spread quickly, forming a dense mat. They thrive in cool, moist conditions, but die back as soon as summer heat arrives. Because of this tendency, plant bluebells among other shade-loving plants, such as hostas and wild ginger. Once the bluebells disappear, other plants can take their place.

Hardy in U.S. Department of Agriculture plant hardiness zones 3 through 8, bluebell flowers are deer and rabbit resistant and have few pest problems. They can also tolerate the toxicity of black walnut trees.They don’t tolerate transplanting well, though, so make sure you plant them in a permanent location.

Planting and Caring for Bluebells

Bluebells grow best in full to partial shade. Plant them en masse under trees and shrubs in moist, but well-draining soil. Amend the soil before planting with compost, manure and peat moss. Bluebells can be started from seed, although they grow quite slowly. Scatter the seed over the garden area in early spring. Keep the soil evenly moist. Bluebells are a type of bulb or rhizome and you can grow them from the bulbs, as well. Plant the bulbs in fall, spacing them 3 inches deep and wide. For faster, more reliable growth, use nursery transplants. Place bluebells in the soil in spring after the last frost. Space the plants 8 to 12 inches apart, depending on the variety. Mulch the soil with 2 inches of wood chips to conserve moisture and slow weed growth.

Water newly planted bluebells frequently to keep the soil evenly moist. Once the roots have become established, you can reduce watering slightly. However, the soil should remain slightly moist to the touch at all times, but never soggy.

Like most native woodland plants, bluebells are adapted to somewhat poor soils and don’t need overly rich conditions. Fertilize them in the spring as new growth emerges with ¼ cup 10-10-10 fertilizer per 100 square feet of soil.

Bluebells spread through both rhizomes and self-seeding. Over time, they can grow out of bounds and become invasive, especially in cool, moist climates. Simply dig the plants out and discard them to keep them in line.

Potential Pests and Problems

Because bluebells appear in spring and disappear by summer, they miss most of the common insect and disease problems that plague other plants. You may notice a few leaf spots, especially during particularly wet springs. Remove any diseased plant material promptly and use soaker hoses instead of overhead sprinklers to reduce disease problems.

Slugs and snails appreciate the same conditions that are best for bluebells – cool, moist and shaded. If you notice slugs, pull the mulch back to dry out the soil slightly. Use traps and bait if the problem is severe.

For more information on bluebells, visit the following links:

Virginia Bluebells from the University of Illinois Extension

Mertensia Virginica from the Missouri Botanical Garden

See Virginia bluebells growing wild on YouTube.

Julie, its ironic we have the same last name